Discover more from Noahpinion

The Great Protest Wave

What lessons can we draw from the global demonstrations that began in 2019?

“whirling, churning; struggling around the dimming, cooling sun” — H.P. Lovecraft

In 2019, the world exploded in protest. There were massive, prolonged demonstrations in Hong Kong, in Chile and Venezuela and Bolivia and Colombia and Ecuador, in Russia and Spain and France, in Iraq and Iran and Lebanon and Algeria, in Indonesia and Haiti. We in the chattering classes spent much of the latter part of that year thinking about the protests, writing about them, theorizing about them, even visiting or joining them. We asked why this was happening. Was it a revolt against inequality? Or authoritarianism? Or was it just a fad enabled by new social media technologies? We felt like we were witnessing something historic, but we couldn’t tell what we were looking at.

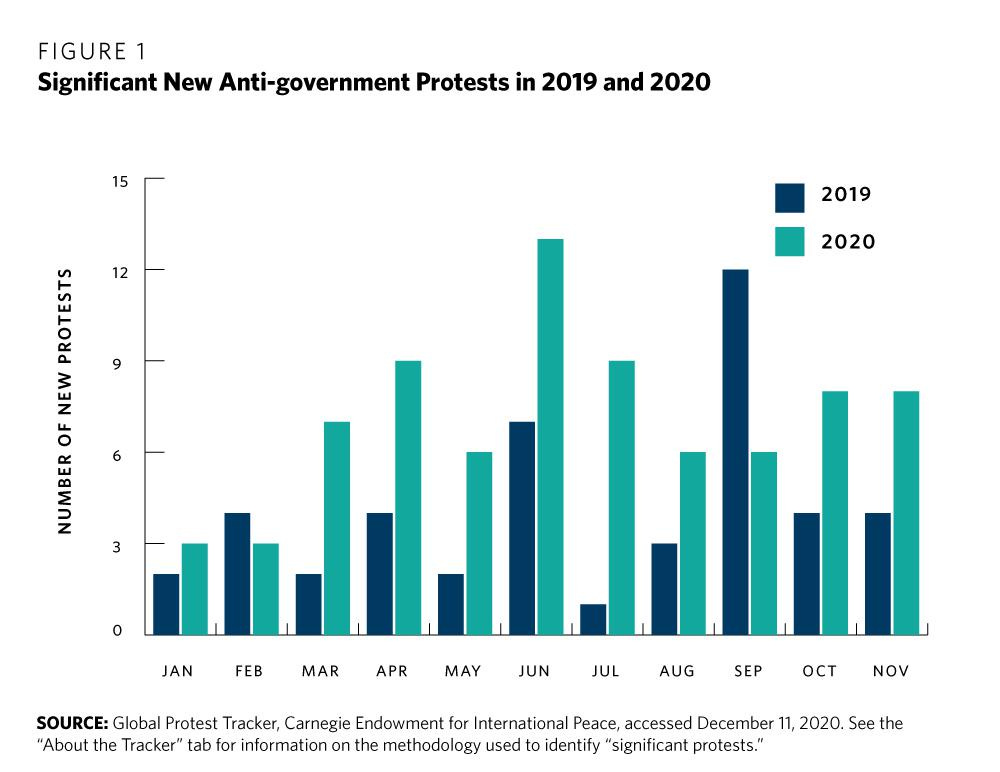

Even the arrival of a once-in-a-century pandemic didn’t douse the flames of unrest for long. The U.S. saw the biggest eruption of protests in its history in the summer of 2020, and those demonstrations were echoed across much of the world. The people of Belarus and Myanmar have poured into the streets in existential struggles against their dictatorial governments. India has had two entirely separate massive waves of demonstrations — one by farmers over agricultural policy, another against a discriminatory citizenship law. Overall, 2020 has seen even more protests than 2019:

You can track ongoing protests with the Carnegie Endowment’s Protest Tracker. At this point there are so many that the map looks like someone spilled orange paint all over it.

Soon, as Covid’s danger wanes, we’re going to wake up and remember that something unsettling is happening to our world.

Why now?

There were quite a few theories as to why the 2019 protests were happening. These could basically be broken down into three categories:

1) The Economic Theory: Economic issues are often a trigger for mass unrest. The farm protests in India are obviously over economics. Chile’s protests were triggered by anger over a subway fare increase, Iran’s by an increase in fuel prices, and France’s by anger over taxes. Some have theorized that the 2019-20 protests were a general revolt against economic inequality. Even in Hong Kong, I saw graffiti expressing anger over high rents.

2) The Political Theory: The protests in Myanmar and Belarus are against leaders who seized or held onto power illegitimately. Hong Kong was about China’s authoritarian encroachment, while Catalonia’s were a separatist movement. America’s protests were about police brutality and racism, while India’s protests over the citizenship law were about exclusion of minorities. Even in Chile, where economic issues were at the forefront, anger at the legacy of the Pinochet government was a factor.

3) The Technology Theory: The various protests have had so many different triggers that some have speculated that technology simply makes protests easier than they used to be. The key technology is social media, which allows outrages to spread rapidly and also facilitates mass ad-hoc organizing. Martin Gurri’s The Revolt of the Public and Zeynep Tufekci’s Twitter and Tear Gas are the key books here.

Personally, my guess is that while all three of these are important, (2) is the dominant one. Economic protests are a common phenomenon, especially in poor countries, but there was nothing particularly bad about 2019 in economic terms. Meanwhile, it seems likely that Twitter and other social media helped spark and organize protests, but there have been massive waves of unrest in the past that required no such fancy gadgetry.

If I were forced to make a conjecture about the most important driver of unrest, Imy guess would be that it was the result of a general realization that bad people are running the world.

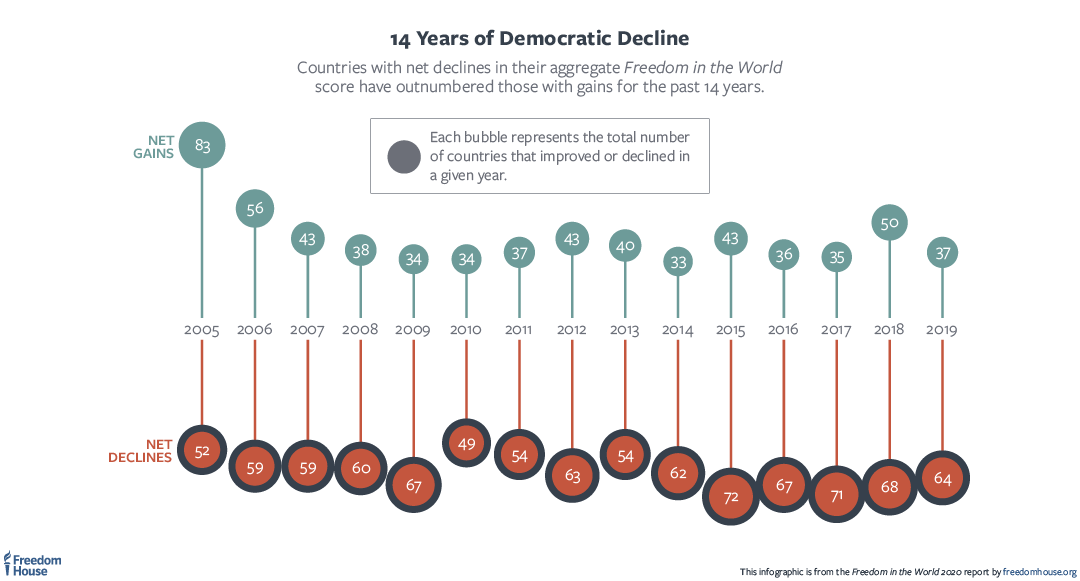

Here’s a graphic from Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2020 report, showing the 14-year-long decline in democracy:

The whole report is worth reading, and they make an explicit connection between declining democracy and unrest.

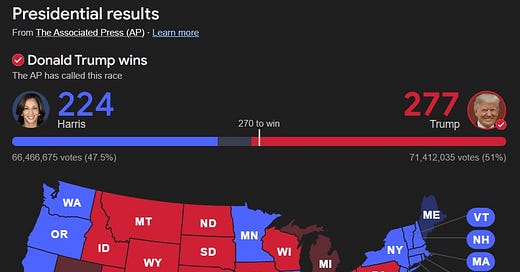

In fact I think there are two aspects to this. First, there’s the shift of power toward authoritarian hegemons. With the invasion of Iraq and the election of Trump, the U.S. has become far less liberal of a hegemon than it was in the late 20th century (it has fallen substantially in Freedom House’s rankings). And the rise of China means that the U.S. is now far less of a hegemon, period. Meanwhile, China itself is taking an alarmingly authoritarian, even totalitarian turn under Xi Jinping, even as the country’s power and confidence builds. Meanwhile, Brexit, the rise of Modi, and a still-powerful Putin mean that it’s hard to find great powers in the world that are clearly still in the liberal camp.

The general feeling that bad hegemons are in charge of the planet could fester in the backs of people’s minds, causing them to strike out at authorities closer to home in the name of democracy, freedom, equality, and so on. And awareness of hegemonic illiberalism is coupled with an awareness of rising authoritarianism closer to home, as many countries embrace their own versions of Trump/Xi/Modi/Putin. The result, according to Freedom House, is that the people of the world are engaged in a “leaderless struggle for democracy” — a struggle that’s both local and global at the same time.

I kind of buy that story, to be honest. That could explain why the protests have seemed to inspire each other, despite being nominally about very different issues. And to underscore the importance and non-triviality of this struggle, it’s noteworthy that more liberal countries have tended to be much more responsive to their protesters.

What have been the results of the protests so far?

To understand this global wave of protests a bit better, I think it’s instructive to look at the various results of some of the protests, and compare them with the general liberal-ness of the countries in which they happened. To make that comparison, I’ll use Freedom House’s scores (a 0-100 scale, with 100 being the most free). Those scores appear in parentheses:

China (9): After a modest initial success (forcing the withdrawal of an extradition bill), Hong Kong’s protests were eventually crushed by a draconian new security law, with many prominent activists arrested. Hong Kong is now suffering an exodus of people and money as the result of a general loss of freedom.

Belarus (11): President Lukashenko has not relinquished power.

Venezuela (14): Supporters of rival presidential claimants have been deadlocked.

Iran (16): The government violently cracked down on protesters, killing an estimated 1500 and suppressing the protests in just three days, though there have been isolated flare-ups since then.

Russia (20): Some very minor political concessions were made. The government was not especially violent in its protest response. There was an attempt to assassinate opposition leader Alexei Navalny. A new wave of protests is now happening.

Myanmar (28): The army, which supports the military coup leaders, has killed hundreds of civilians and appears intent on violently suppressing the protests while making no concessions.

Iraq (29): Protests were met with violence, but forced the resignation of the prime minister and changes to the election law.

Algeria (32): Various politicians resigned, and there were legal changes to strengthen the judiciary and the legislature.

Lebanon (43): The prime minister and various other politicians resigned.

Ecuador (67): The government reversed the austerity measures that sparked the protests.

India (67): The police were fairly violent in their response to the citizenship law protest, killing dozens. The government did not rescind the citizenship law or make other concessions. As for the farmers’ protest, there were a few modest legal concessions made.

United States (83): Police responded to protests with widespread but mostly nonlethal violence, which was widely condemned. Various police reform measures have been introduced in cities, and both companies and the government have committed to a variety of anti-racism measures. Democrats are attempting police reform at the national level.

France (90): Various taxes were reduced or cancelled.

Spain (90): Catalonia has not been granted independence.

Chile (93): Police responded with occasionally lethal violence. Eventually various egalitarian economic reforms were announced, as well as a plebiscite to write a new constitution to replace the current one written under Pinochet.

Though the pattern isn’t absolute, you can see that countries that are more free (by Freedom House’s definition) tended to be less brutal toward protesters and offer greater concessions to protesters’ demands. India’s brutality and intransigence and Algeria’s liberalizing response are exceptions here, but overall protests seem to have a much higher chance of succeeding in more liberal countries.

If we look at the global unrest as a general backlash against the encroachment of authoritarianism and unfreedom, we can see the protests as a sort of test of local regimes. Overall, liberal regimes are passing the test and illiberal regimes are failing it. It really does matter what kind of country you live in.

This pattern is both encouraging and discouraging. On one hand, it means that liberalism is in some sense still doing its job, responding to popular sentiment by accommodating the people’s wishes. On the other hand, the fact that liberalism itself is diminishing means that this benefit will probably weaken. And more worryingly, unlike in the 1980s and 1990s when many protests toppled illiberal regimes and replaced them with more inclusive ones, today’s protests are generally not succeeding in forcing liberalization.

And the most worrying question of all is whether this unrest is actually a prelude to something far more destructive.

Its hour come round at last

Many previous waves of unrest have heralded outbreaks of war. The Arab Spring led directly to wars in Syria, Yemen, and Libya that have claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. The unrest at the end of the Cold War presaged a decade of post-Soviet conflicts. Of course the 1920s and especially the 1930s were times of great unrest around the world, much of which fed into the cataclysm of World War 2.

One possibility that was discussed a lot during the Trump era is a second U.S. civil war. Undoubtedly the possibility that unrest will lead to a national collapse and a protracted struggle is still on many people’s minds after the coup attempt of January 6th. A U.S. collapse would in turn leave a global power vacuum that would probably give rise to all kinds of conflicts — much as the USSR’s collapse did in the 90s, but on a much vaster scale, especially given that in the 90s the U.S. was still there to provide some stability. Regional powers would fight regional conflicts, China would assert hegemony over Asia, Russia might try more military adventures, and so on. Nuclear proliferation might be rapid.

Alternatively, it’s possible that the current era of unrest will end in a world war, like the 1930s did. All the ingredients are there for a clash between the U.S. and China over Taiwan in the imminent future. Or China could get in a fight with India over their disputed, militarized border, or with Japan over disputed islands. A world war could arise as a diversionary war, with countries embracing international conflict as a release valve for anger at home.

But as I said in the previous section, I suspect that the global protests are actually an attempt to battle back against the illiberalism creeping over their world. And I think that illiberal regimes, rather than protests, are the biggest risk for war. Democratic peace theory might or might not be right in general, but it’s clear that a world ruled by Xi, Modi, Putin, and someone like Donald Trump would not be a safe one. If regimes like these do end up going to war, we might remember the protest wave that began in 2019 as a failed last-ditch attempt to stop it.

I think the thing with Brexit is that it plausibly has the same causal factors as the rest of populist and authoritarian global trend, while at the same time definitely not being in the same category of antidemocratic and authoritarian that Trump, Modi, Xi are in.

Hey Noah

On the role of tehcnology, I also recommand this book

https://www.amazon.fr/Hype-Machine-Disrupts-Elections-Health/dp/0525574514

In it, S Aral mentions the 2011 protest in Russia where a natural experiment occurred

and cites a paper show that digital technology can cause protests as well

( link toward the paper https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3982/ECTA14281)