Discover more from Noahpinion

Welcome to the UFO wars

The strange new skies are buzzing with balloons and drones, and the U.S. is scrambling to catch up.

A bizarre high-tech battle has suddenly broken out in the skies all over the world. In the week since the U.S. shot down China’s big spy balloon, three smaller objects have been shot down — a cylindrical object over Alaska on February 10th, another cylindrical object over Canada on the 11th, and an octagonal object over Lake Huron on the 12th. Other spy balloons have been spotted all over the world. China, meanwhile, has accused the U.S. of sending its own spy balloons over its territory, and threatened to shoot down an unidentified object near Qingdao and possibly another near Shandong.

This may come as a disappointment to the sci-fi enthusiasts out there, but the U.S. and China aren’t cooperating to defeat an invasion by space aliens. What’s happening here is that for years, China was flying spy balloons over the U.S., which people were mistaking for UFOs (or UAPs, as they’re now called), and the U.S. was either intentionally or unintentionally letting them pass. One theory is that there are simply a lot of balloons up there, and the U.S. military didn’t want a bunch of false alarms. Another is that the U.S. simply failed to have its radars keep track of slow-moving objects. But whatever it is, the massive uproar over the big spy balloon obviously prompted the U.S. to get serious about detecting and downing the floating intruders.

Anyway, if you want to read more about the spy balloons, I recommend reading the work of Tyler Rogoway, who was shouting about this topic long before most people were paying attention. Here’s a good thread about the recent intrusions, with some links to some earlier articles he’s written:

Rogoway emphasizes that balloons aren’t the only strange thing zipping around the modern skies. Drones, and drone swarms, are also important. Both balloons and drones command regions of the air that the 20th century technologies of jets and satellites largely left empty — the former occupy the “near space” region above where airplanes traditionally fly, and the latter command the space below 2000 feet.

In other words, the entire sky is now a contested space. Especially low to the ground, the U.S. no longer has the ability to deny access to China’s unmanned aerial forces. Swarms of probably-Chinese drones buzz U.S. Navy ships and nuclear power plants in Arizona. The head of U.S. Special Operations Command summed it up when he said: “I never had to look up before”.

Anyway, welcome to Cold War 2 — it’s only going to get stranger from here. And just as in Cold War 1, when the U.S. reoriented its economy to ensure parity with the Soviets in the aerospace industry, we’re going to have to make big changes to keep up with China in the drone race. Unfortunately, right now the U.S. has either fallen behind China, or risks falling behind, in almost every key emerging industry and technology involved in that race.

Drones are the convergence of three technological revolutions

Balloons and drones are currently being used for spying, but they can also be used for warfare. In Ukraine, Iranian Shahed drones bombard Ukrainian cities, Orlan and Lancet drones help Russian artillery find its targets, and Ukrainian quadcopters drop explosives on unsuspecting Russian soldiers. Drones have become essential equipment for every fighting squad. (I’m sad to say I predicted this a decade ago.)

But this is only the beginning. The Pentagon is trying to develop huge swarms of thousands of autonomous combat drones. China is creating a drone mothership. Drones are also being used in assassination attempts, and it’s only a matter of time before autonomous drones are used for this as well. Loitering munitions — a euphemism for suicide drones — may soon become the main method of attack against the armored vehicles that dominated last century’s battlefields. China is already trying to make autonomous swarms of these. (Of course, all this is in addition to the high-powered hypersonic drones and uncrewed ships and aircraft and submarines and satellites that will occupy more traditional battlespaces.)

Drones, spy balloons, and other unmanned vehicles basically need three technologies. They need propulsion, to move them and their payloads and equipment around. They need guidance, to get them where they’re going. And they need communication, to provide guidance, to relay information back, to change their orders, and so on. The reason drones are experiencing such a Cambrian explosion right now is that there have been technological revolutions in propulsion, guidance, and communication all at the same time.

Fast drones, like missiles, use good old rocket or jet propulsion. But for small drones or slow balloons, batteries are really the key. They allow energy to be shipped in smaller packages, they allow quieter machinery for stealth, and electric motors can apply very high torque. In the 2000s, lithium-ion batteries became more efficient, and in the last decade, they have suddenly become much, much cheaper.

This could be only the beginning, too; with Li-ion batteries becoming so economically important, tons of research-labs are working on the next generation of batteries.

For guidance, the big revolution is AI. Currently, drones like the U.S. Air Force’s famous Reaper are controlled by rooms full of human beings. Better computer vision will allow those drones to do their own targeting, seeing concealed vehicles and soldiers that human eyes would struggle to pick out, distinguishing decoys from real targets, and pursuing moving targets at speed. And AI will eventually allow full autonomy — the long-imagined “killer robots” that you see in sci-fi movies will become a reality.

For communication, the revolution is just a bunch of networking technology. Broadband and cell towers were built out in the 2000s and 2010s, 5G wireless and satellite networks like StarLink are being built right now. All of this infrastructure was built for civilian use, to let us argue on social media and watch boring fantasy TV series on Amazon Prime. Now it will be used for the drone wars.

It was kind of a coincidence that better batteries, AI, and networking technologies all experienced major revolutions at about the same time. But given that they did, it was kind of inevitable that uncrewed vehicles would represent the convergence point of all three. Unfortunately, the U.S. is either lagging behind China, or in danger of falling behind, on all of these technologies.

The U.S. is behind in almost every drone-related industry and technology

My basic interest in technological competition came from my interest in industrial policy. At some point I realized that national security, rather than climate change or jobs or a love of new technology, was going to become the most important factor in the U.S.’ shift away from laissez-faire toward active intervention in its economy. So in recent months I’ve been trying to read a bunch about which technologies and industries the U.S. is competing with China for, and who’s winning the competition.

Obviously one very important technology is semiconductors, which underlie most other advanced technologies. The U.S. and its allies have a pretty commanding position there, and new export controls will help keep China from catching up. But in all the newer technologies that have fueled the drone explosion, the U.S.’ position looks shakier.

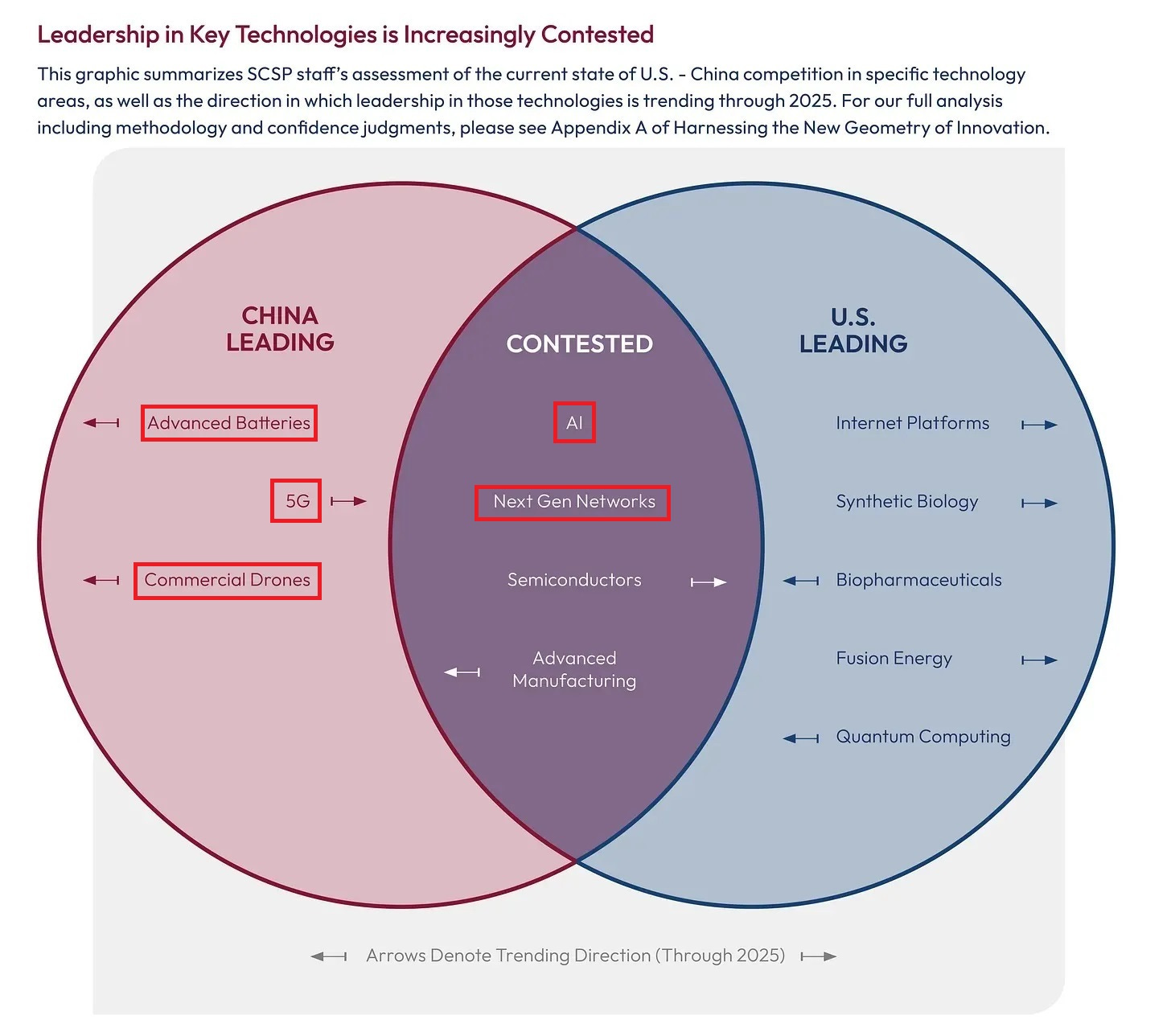

Here I like to refer to the Special Competitive Studies Project’s diagram showing the general state of play:

I drew red boxes around the key drone technologies (other than semiconductors). Though the U.S. leads in many areas, these are the ones that favor China.

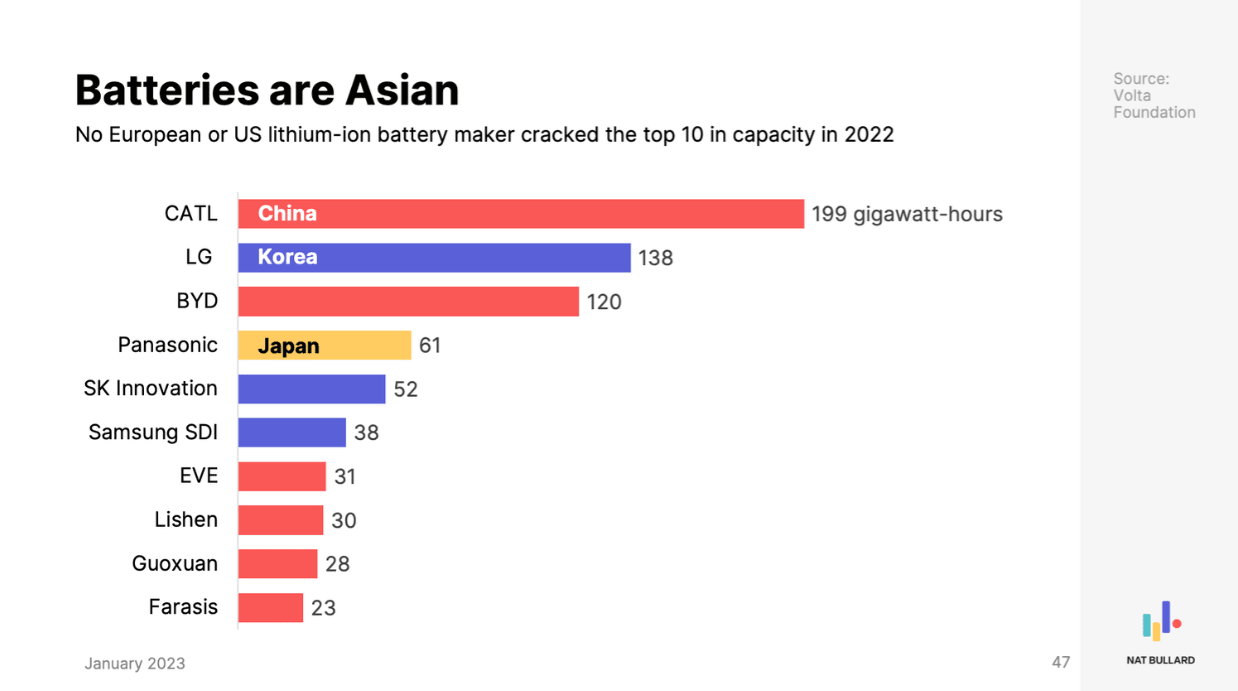

For example, batteries. Korea and Japan make some lithium-ion batteries, but China’s companies outweigh them, and their dominance has been growing.

One reason for this is that China is emerging as the world’s largest EV maker, so that’s where the demand for batteries is. Another is that China controls the processing of many of the minerals that go into batteries, since these are low-margin high-volume capital-intensive industries that most countries’ businesses don’t want to touch. U.S. research labs may be ahead in terms of inventing better batteries, but China has been able to scale the cheap stuff. And for making massive drone swarms, scaling is what matters.

On 5G, China’s flagship electronics company Huawei has captured much of the global market, thanks to a combination of hard work, talent, high research spending, government-aided corporate espionage, and massive government subsidies to underbid competitors. The book Wireless Wars tells this story, and why Western telecom companies fell behind. The new semiconductor export controls will probably curb Huawei’s momentum to some degree, but it’s still the unquestioned 5G leader. And it’s putting a lot of research and effort into 6G as well.

As for AI, the U.S. has zoomed ahead in the field of generative AI — large language models and AI art. But in the field of computer vision, Chinese teams have been quietly raking in top awards. Computer vision is a field where massive data matters a lot, and China’s ubiquitous, often intrusive tech ecosystem delivers it more video and photo data than anyone else. In autonomous vehicles, China may be edging ahead, due to greater willingness to tolerate risk on the road. It’s not clear that the U.S. is behind in the types of AI that will have the greatest relevance for the drone war, but there’s little sign that it’s ahead.

And finally, China is ahead in the manufacture of commercial drones themselves. While the U.S. does well in fast, powerful drones that substitute for traditional airplanes, and while it has some defense contractors like Anduril and Skydio that are working to plug holes in its capabilities, China is the master when it comes to commercial drones. As of 2021, a single Chinese company, DJI, had a 76% global market share in these drones. It’s these drones that Ukraine has used to engage Russian infantry directly on the battlefield. China dominates this industry simply because it’s low-margin and scale-intensive, and all the suppliers for the parts are located in China. Incidentally, China has taken the lead on the export of bigger, faster drones as well.

The U.S., of course, will try to catch up or take the lead in all of these technologies and industries. In battery manufacturing and commercial drones it will likely fail to catch up, because the U.S. economy is uniquely bad at subsidizing capital-intensive low-value-added manufacturing industries. But it will probably get a foothold, and its Asian allies will give it some added heft. Thus, it is very important that the U.S. maintain a respectful, constructive, cooperative relationship with South Korea and Japan, rather than alienating them with go-it-alone trade policies that pit the U.S. against its allies.

In AI and 6G, semiconductor export controls will help a bit, but the U.S.’ main advantage is that it has most of the world’s top researchers (including many who were educated in China). So if the U.S. keeps pouring research funding into AI and networking, forces the regulatory state to make way, and doesn’t stupidly give up its secret weapon of large-scale high-skilled immigration, its chance of retaining or retaking the lead in these areas seems good.

War of the flying expendables?

One interesting thing about the new war of the balloons and drones is that all the relevant technologies will probably be battle-tested in real time without a full-scale war. Usually, the only way to really know how a military technology — tanks, or bombers, or precision munitions — performs in the field is to actually go to war (this has occasionally led to cynical accusations that the U.S. starts wars just to test the military-industrial complex’s shiny new toys). But with balloons and drones, we could get to see them tested out pretty frequently.

The simple reason is that balloons and drones are cheap and expendable. They cost relatively little money and no lives, so both the U.S. and China are probably willing to lose a lot of them even in peacetime. Right now the balloons are being shot down by expensive missiles flown by expensive jets, but I’m confident that cheaper methods will soon be developed. And there’s little danger that destroyed balloons or drones will escalate to war.

So over the next couple of decades, it seems fairly likely that we’ll see a constant, low-intensity battle for the skies. Just as cyberattacks have faded into the background noise of great-power conflict, so might downing of balloons and small drones go from an international incident to a reasonably frequent occurrence. This would allow the U.S. and China not just to gather intelligence on each other, but to test their own systems’ capabilities and improve them in an iterative fashion.

In other words, welcome to the UFO Wars. Above and below the serene layers where the airplanes still soar undisturbed, the once-quiet skies of our planet have come alive with mysterious objects and small, furtive, high-tech duels. We have met the aliens, and they were us.

Hey Noah. Skilled immigration, industrial policy, and DARPA like programs seem to be the only way the US can compete.

But China wins with sheer scale and low cost manufacturing.

I know you mention this in the post. But any appetite to write more about the policy decisions the US has to make to catch up?

Essentially - what do we do about it?

I would push back a little on the relevance of China's supposed lead in advanced batteries.

China is able to manufacture commodity lithium-ion batteries in vast quantities more cheaply than anywhere else in the world. But you don't need vast quantities of batteries to build a lot of small drones, and big drones are going to be powered by combustion engines or possibly fuel cells because of the order of magnitude improvement in capability a combustion engine offers compared to electric power.