Discover more from Noahpinion

Life in the New American Suburbs

A vision of how we'll live in an age of moderately higher density

“Outside a new day is dawning

Outside suburbia's sprawling everywhere

I don't want to go, baby”

— Kim Wilde

Conor Dougherty is perhaps the best chronicler of America’s battle for denser housing. I heartily encourage everyone to read his recent article in the New York Times, entitled “Where the Suburbs End”. It recaps the story of how Americans fled cities to live in sprawling suburban neighborhoods zoned for single family homes, and how that model of urbanism is now slowly coming to an end.

The reason for this, of course, is that the suburban model we created was fundamentally unsustainable. The upkeep on the vast sprawl of roads and other infrastructure was hellishly expensive, especially given the country’s excessive construction costs. New knowledge industries created clustering economies that made density more important for productivity, even as social media and a decline in crime made urban life more enjoyable. And the housing crash of 2007-8 showed that the model of sprawling ever farther outward from city centers had come to its limits — from now on, new Americans must mostly be put into existing urban spaces, which means density. These pressures have created both a rental crisis for renters and an affordability crisis for first-time homebuyers.

The suburban model of the mid 20th century, however, came with a set of laws and institutions designed to protect it against future encroachment — urban fragmentation that enables powerful local homeowners to block new development, and a thicket of formidable zoning regulations, parking requirements, setbacks, height limits, and other regulations. Those who realize the need to create a denser America have only begun to hack through that tangle, and resistance is fierce.

But as Dougherty notes, the victories are slowly piling up — most recently and perhaps most notably, SB 9 and SB10, two new California laws that end single-family zoning by allowing duplexes everywhere, upzone areas near transit hubs, and streamline the permitting process for this new housing. Other states are passing similar laws.

These new laws will not turn the U.S. into Japan, where efficient networks of trains weave “suburbs” denser than Brooklyn into huge megalopolises, and housing is affordable because developers are empowered to build as much as they want. But they will change the suburbs — especially the inner-ring ‘burbs that lie between dense urban centers and far-flung exurban sprawl. As Dougherty puts it:

Across America, housing is for the most part built in one of two familiar ways. The first is [exurbs] outside the urban center [with] wide streets and cul-de-sacs named after trees. The second is…a glass condominium tower or high-rent apartment building.

In the vast zone between those poles lie existing single-family neighborhoods…which account for most of the urban landscape yet remain conspicuously untouched. The omission is the product of a political bargain that says sprawl can sprawl and downtowns can rise but single-family neighborhoods are sealed off from growth…

And now [that bargain is] being torn up.

The suburbs will not vanish as a result of America’s new need for density; they will simply change. But what will they change into? What will the new suburbs look like, and what will the lives of people in them be like? Obviously there will be a wide variety, but I think that current trends are starting to sketch us a rough outline of that future.

I think it’s very important to spin concrete visions of how Americans will live and commute and work and play in the future. This is different from spinning fantastical visions of what our cities might look like if we had carte blanche to rebuild them however we saw fit — the solarpunk dream. Political constraints and cost constraints are very real things, and the somewhat-denser future we’re going to get is not the same as the much-denser utopia that many urbanists and YIMBYs would like. It’s going to be significantly better, but not infinitely better.

Here’s a taste of where I think we’re headed.

Where we’ll live

The newer, denser suburbs will have roughly the same layout, but single-family housing will be replaced with a mix of housing. New state-level housing bills like SB9 and SB10 are mandating legalization of things like accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and duplexes. But near transit hubs, they’re legalizing even more dense forms of housing, like apartment complexes. And some cities will choose to allow more density than the state governments mandate. Thus, the new suburban landscape will generally include:

single-family homes

single-family homes with ADUs

duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes

row-houses

low-rise apartment buildings

During a trip to Seattle last year, I noticed a fair amount of that housing going up in the neighborhood of Queen Anne. Here are some pics from that neighborhood, courtesy of my friend Wally Nowinski:

Note how these construction styles generally preserve the feeling of the existing suburban construction based around single-family homes. There are trees lining the streets, with cars parked out front. The dwellings are somewhat set back from the street, and are mostly constructed in ways that make multi-family housing resemble single-family housing in construction style.

In other words, the feel of the suburbs won’t be that changed from what it is now. The plots that have housing now will simply have more housing, at the expense of yard and a little bit of sky. The streets will remain the same, the commercial areas will largely remain the same. There will simply be more people.

So what does this really change? First, it allows us to fit more people into existing areas, which is economically necessary. Second, it will lead to a greater mix of classes in neighborhoods — if local suburban amenities are the same, smaller units will necessarily be cheaper than larger ones. You’ll have working-class families, students, and young people living in apartments and ADUs, higher-earning folks living in duplexes and row-houses, and a combination of well-off folks and legacy homeowners in the single-family homes.

This is a somewhat more egalitarian vision of suburban America, but it also means that some of the “neighborhood character” that incumbent homeowners are used to — and that they fight so hard to protect — will be sacrificed. Having young people and college kids and working-class families in your leafy suburban neighborhood really does make it a different place (a better place, I would argue). And greater density will provide some other benefits, such as more people knowing their neighbors.

But we shouldn’t get too excited about these changes. There will still be nicer and worse neighborhoods, gradations of class and price and “good schools” and other markers of desirability. (Remember, I’m not describing how I wish America would be, but merely predicting how it will be.)

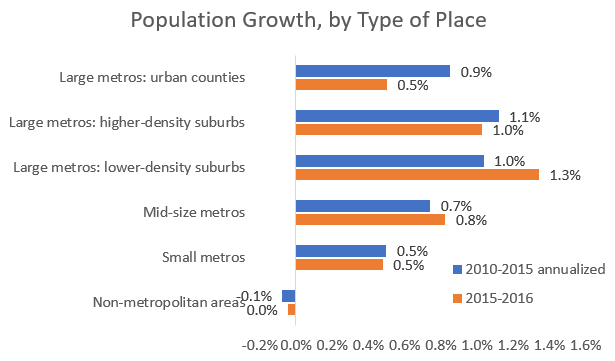

The real key here is that despite greater density, the suburban way of life will be mostly preserved. And the fundamental reason it will be preserved is that Americans really really like living in the suburbs. During the mid-2010s, at a time when city centers were becoming insanely overpriced and everybody was talking about moving to the city, Americans actually moved out to the ‘burbs on net:

The desire for suburban living is overwhelming, and the only way to square that with the economic need for greater density is to have a whole lot of neighborhoods that still feel like suburbs but fit more people.

How we’ll get around

There are basically two issues when it comes to transit: How people get around the place they live, and how they get to other places.

The densification of the suburbs will put pressure on road networks. Street parking will become more scarce, and streets will become more crowded. That will make car ownership less desirable, because parking will become more expensive and traffic will become more of a problem (though many streets will put in speed humps to limit car traffic and increase safety, which will also make driving more onerous).

This will lead to several developments. First, more people who work in the city center — or in another suburb — will want to take the train instead of drive. That will require commuter rail — fast trains that go into the city center from suburban hubs. The Bay Area already has two commuter rail systems — BART and Caltrain. With more people wanting to ride such trains, there will be pressure to add service and build more stops. That will happen.

A second change is that driving around town will become less popular. Some people — especially young people and lower-income people — will decide to ditch their cars in favor of e-bikes, bikes, and electric scooters. The rise of batteries has come just in time to give people a variety of local transportation options. Even some higher-income people may choose to go car-free for reasons of health, safety, and lower stress — biking to the local commuter rail station to go into the city, biking or walking to local shopping villages, and so on.

Of course, most people will still own cars, though the cost of doing so will go up. Cars will therefore be somewhat more of a mark of status, though this will be mitigated by the fact that many of the cars will be hidden inside parking garages instead of displayed in driveways. I predict that change will erode the culture of conspicuous consumption that has grown up around the American automobile, which will hopefully help people feel more comfortable about embracing alternative modes of transportation.

Where we’ll work, shop, and play

If fewer people are willing to drive long distances, that will increase the demand for retail near where people live. Also, increased housing density means that suburban restaurants and shops will more easily be able to get customers, wherever they are.

The new suburbs will thus probably have fewer malls and strip-malls, and more shopping villages that people can walk, bike, or scooter to. I’m talking about a single shop-lined street or a small walkable complex located near to where people live. It’ll have a coffee shop — Peet’s or Dunkin Donuts, depending on the socioeconomic class of the area — some clothing stores, some restaurants, and so on. It’ll have some parking lots and street parking for the people who choose to drive in, but nothing too monstrous.

Around the commuter rail stations, larger shopping complexes will be common — big-box stores and malls. This is because the rail stations will be centrally located, zoning rules will likely be relaxed, and high-density housing will be located nearby.

As for where people work, this of course depends on how much the country transitions to remote work in the post-pandemic age of Zoom and Slack. My guess is that although some people will go fully remote (and disperse around the country), most people will still go into the office 2 or 3 days a week. On the other days, they’ll need some place to work. Some will work in their homes, though this will be harder in a small apartment than a large house. Some will work in cafes and co-working spaces, so I expect these to proliferate in the new suburbs.

In terms of play, there will be more options in the new denser American suburbs. Greater density means young people will more easily be able to meet friends and find dates nearby, with the aid of apps. E-bikes and scooters will make young people more mobile as well, and better commuter rail will allow them to go into the city without driving drunk. For older folks, there will be a greater variety off restaurants nearby, and the new suburbs should be able to preserve parks and open space without too much crowding.

A moderately better urban future

The densification of the suburbs that I envision here will not solve all of the problems of American urbanism. There will still be some segregation by class and race. Good local train networks like those enjoyed in Europe and Asia will still be far too few, and cars too common. The suburbs will still be too distant to form a truly efficient urban network. America will not become the Netherlands, and it will not become Japan.

But things will be moderately better. Housing will be a bit more affordable, living near to a knowledge industry center will be a bit easier, cars will kill somewhat fewer people. More people will know their neighbors, and life in the American suburbs will be less socially isolating and stultifying.

This future will still be a place that people complain bitterly about. Urbanists will still decry cars and call for more trains and more density, even as suburbanites fight to preserve their quiet leafy streets. America will still have precious few thrilling hyper-dense metropolises along the lines of Manhattan, Tokyo, or Amsterdam. Perhaps someday, but not soon. Yet this moderately better future of somewhat denser suburbia will be something that many Americans fought bitterly and sweated blood to achieve. The forces of inertia are vast and entrenched, and the forces of change are forever charging up unfavorable ground.

This is basically Arlington, VA, where I live (or at least a lot of it). And it's one of the safest, most affluent, most diverse, and physically healthiest places in the country. I like this future!

One element you left out: I think we're a few years out from the beginning of pressure for the state to enable Accessory Commercial Units in the way that it has enabled ADUs. For many of the R1 zones, 80+% of the people living in them are an unreasonable walking distance from any commercial hub. The only way you turn those into 15-minute neighborhoods is to allow corner stores and cafés to be opened by residents on formerly-exclusively-residential parcels, where it is presently illegal to operate a business.

https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2020/8/15/accessory-commercial-units

When I was a kid, I remember my family got our hair cut in the basement studio of a walking-distance neighbor. I think we're going to see a lot more of that in the future.